The Top 10 Journalism Movies of All Time — Based on the Actual Journalism in the Movie

By Prof. Adam L. Penenberg

Director, American Journalism Online (AJO) Master’s Program at NYU

There’s a strange feeling that comes with watching a movie about journalism when you’re a journalist, especially when it’s about a story you actually reported—and doubly so when you’re a character in it.

That was my experience with “Shattered Glass”, the 2003 film that dramatized the rise and fall of Stephen Glass, a young journalist who fabricated dozens of stories at The New Republic. I helped break the story that unraveled his career, and when I first watched the film, I was faced with an almost out-of-body experience: Steve Zahn, an actor known for playing lovable losers with substance-abuse problems, portraying me. He wore what I wore and said things that I said, as he retraced my steps, clicking through the same links, making the same calls, having the same discussions, hitting the same walls.

By Hollywood standards, “Shattered Glass” is one of the more accurate portrayals of journalism. The filmmakers took great care to get the details right, from the mechanics of fact-checking to the way Glass manipulated his editors. But even in a movie that stays true to the facts, there are embellishments, simplifications, and moments that didn’t quite happen the way they’re depicted on screen. That’s the nature of film: journalism is often slow, methodical, and full of dead ends—hardly the stuff of a tight 90-minute thriller. And yet, when journalism movies get it right, they tap into something deeper than just facts: the dogged pursuit of truth, the weight of responsibility, and the sheer thrill (or terror) of breaking a story that matters.

The best movies don’t just capture how journalism works—they capture why it matters. I still get emails and messages from people who’ve just seen “Shattered Glass” for the first time, congratulating me on the story, as if it didn’t happen more than two decades earlier. The film is a staple of high school and college syllabi around the world, which means I’m regularly invited to classrooms to talk about it. There is even a podcast devoted to the movie.

Clearly, the story had an impact. It was a watershed moment for online journalism, proving that digital outlets could not only break major stories but take down established print institutions in the process. It helped usher in a new era of media accountability, one where fact-checking wasn’t just an internal newsroom process but something anyone with an internet connection could do. And it’s why I’m still talking about a story I wrote in the dial-up era, and now a whole generation knows me as “the guy played by Steve Zahn.”

These films don’t merely depict history—they become history, shaping how the public remembers the real events and sometimes distorting reality in the process. Most people probably know the Stephen Glass story because of “Shattered Glass”. In the same way, “All the President’s Men” is the Watergate story for generations of Americans, even though it relates only a fraction of what happened. Movies like “Spotlight” and “The Insider” take meticulous care to stay true to the facts, but inevitably, they simplify, rearrange, and dramatize. The result is that the film version of an event often becomes more widely accepted than the real, messy, complicated version that played out in newsrooms and on the ground.

With that in mind, here’s my list of the top 10 journalism movies of all time—not ranked, mind you, because how do you compare taking down a president to exposing systemic abuse in the Catholic Church? Instead, I have divided them into three categories and chosen them based on a simple but essential criterion: they all had to be based on true events.

That’s why you won’t find films like “The Paper” or “The Year of Living Dangerously” here—great movies, but fictional stories. And while “Newsies” is beloved by theater kids everywhere, it’s about newsboys, not journalism.

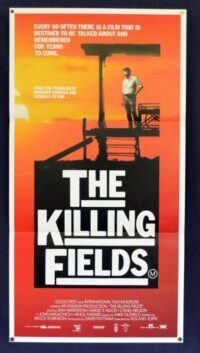

The films on this list aren’t just about reporters doing their jobs; they are about real journalists doing real journalism. Some show how truth prevails (“All the President’s Men”, “Spotlight”). Others reveal how it can destroy the journalist (“Kill the Messenger”, “Capote”). Some highlight the war between truth and power (“Good Night, and Good Luck”, “The Insider”), while others show the dangers of mistaking narrative for reality (“Shattered Glass”, “Zodiac”). Then there are those that remind us that, in the end, truth alone doesn’t always bring justice (“The Killing Fields”, “A Private War”).

Ultimately, these films aren’t just about journalism. They’re about human nature, the best and the worst of us. Ultimately, they remind us that exposing the truth almost always comes at a cost. Somebody has to pay. Otherwise, deception wins.

Please view the official press release here.

I. The Process: How Journalism Actually Works

These films capture journalism at its most relentless—where methodical reporting, painstaking verification, and sheer persistence don’t just uncover the truth, they expose corruption, bring down the powerful, and force the world to reckon with what it tried to ignore. Whether it’s taking down a president (“All the President’s Men”), shattering the silence of a global institution (“Spotlight”), or chasing a story that may never have an ending (“Zodiac”), these films show that real journalism isn’t about speed—it’s about refusing to yield to the forces determined to silence it.

“All the President’s Men”

“All the President’s Men”

The granddaddy of all journalism movies, this film defined the way generations of people (and probably more than a few reporters) think about investigative journalism. “All the President’s Men” (1976) is the story of two Washington Post reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, who uncovered the Watergate scandal, ultimately bringing down a sitting U.S. president. But what makes it the gold standard isn’t just its subject matter. It’s how faithfully it captures the process of reporting: the dead-end phone calls, the reluctant sources, the frustration of knocking on doors only to have them slammed shut. It’s a movie about journalism that actually feels like journalism.

At the time of Watergate, the idea that reporters could take down a president was unprecedented. Woodward and Bernstein weren’t famous when they started—just two young reporters who had the luck (or misfortune) of getting assigned to cover a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters. But as they dug deeper, the story led them to something far bigger: a vast web of corruption, illegal surveillance, and dirty tricks orchestrated at the highest levels of government. Their reporting, and the work of others at The Washington Post, ultimately forced Richard Nixon to resign.

The film gets a lot right about the mechanics of investigative journalism. Unlike many movies that depict reporters chasing down leads in a flurry of high-speed car chases or last-minute courtroom showdowns, All the President’s Men is a masterclass in restraint. Much of it takes place in quiet moments: Woodward (Robert Redford) and Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) flipping through phone books, scribbling notes, and whispering into pay phones. One of the most suspenseful scenes involves nothing more than Woodward meeting his anonymous source, Deep Throat, in a dark parking garage, where he receives cryptic warnings about just how deep the conspiracy goes.

But for all its accuracy, the film still takes creative liberties that shape how people imagine journalism—sometimes in ways that aren’t quite right. For one, it presents investigative journalism as a largely solo endeavor, with Woodward and Bernstein cracking the case through sheer persistence. In reality, The Washington Post’s Watergate coverage was a team effort, with dozens of reporters, editors, and legal experts working behind the scenes. Ben Bradlee, played as a gruff but supportive editor, was actually far more skeptical in real life and demanded more verification before running key parts of the story. The film streamlines the work of an entire newsroom into the efforts of two heroic reporters, which makes for a great film but a somewhat misleading portrait of how major investigations unfold.

On a more human level, while the movie builds tension around the risks Woodward and Bernstein faced—anonymous threats, secretive meetings, warnings from Deep Throat—it never really shows the personal toll the investigation took on them. In reality, they were under enormous pressure, facing criticism from the Nixon administration, rival media outlets, and even some of their own colleagues who questioned whether they were chasing a phantom scandal. The film suggests they charged ahead with confidence, but in real life, they wrestled with doubt.

Ultimately, “All the President’s Men” subtly reinforces the idea that journalism is about exposing the truth and watching the bad guys fall. While Watergate did lead to Nixon’s resignation, many investigative stories don’t have such clean endings. Reporters can publish blockbuster exposés that shake institutions, yet see little change. Corrupt figures often survive scandals, and consequences are rarely as swift or dramatic as they were in the Watergate era. The movie ends triumphantly, but the reality of investigative reporting is often murkier and far more frustrating.

Would this kind of investigation unfold the same way today? Yes and no. The fundamentals like verifying sources, following the money and uncovering hidden documents haven’t changed. But the tools have. Woodward and Bernstein relied on landlines, typewriters, and face-to-face meetings. Today, a major government scandal would be unraveled through leaked emails, hacked documents, and digital forensics. Deep Throat might not whisper in a parking garage. He’d drop an encrypted file on Signal.

Despite these changes, “All the President’s Men” remains the blueprint for investigative reporting, not because of its era-specific tools, but because it shows the sheer persistence required to break a big story. It’s not glamorous. It’s long hours of grunt work, hitting roadblocks, getting people to talk who don’t want to, and piecing together fragments of truth until the full picture emerges.

More than any other film, “All the President’s Men” set the gold standard for how the public imagines investigative journalism. It shaped the mythology of the fearless reporter, the dogged pursuit of truth, the idea that journalism is a check on power. That mythology isn’t always accurate. Reporters get things wrong, stories fall apart, and the powerful don’t always face consequences.

Every journalist who has ever knocked on a door or asked a tough question knows one thing: the work Woodward and Bernstein did still matters. The movie that immortalized it does, too. The Cost: When the Journalist Becomes the Story.

Spotlight

Spotlight

“Spotlight” (2015) isn’t just one of the best journalism movies ever made—it’s one of the most accurate. It doesn’t just get the facts right; it gets the feel of investigative journalism right. The drudgery. The dead ends. The way big stories don’t start with a bombshell tip but with a nagging sense that something isn’t adding up. The way reporters chase details that might go nowhere, knock on doors that might not open, and read through old court filings in a basement long after everyone else has gone home.

The film tells the true story of how The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team uncovered the Catholic Church’s cover-up of child sexual abuse, an investigation that exposed not just a handful of predatory priests but a systemic conspiracy stretching from Boston to the Vatican. This was the kind of story that shakes institutions, the kind that makes people furious, that sparks denial and outrage before finally forcing a reckoning. It won the team the Pulitzer Prize. It also shattered trust in the Church in ways that are still being felt today.

How well does “Spotlight” capture the reality of the reporting? The film sticks remarkably close to the truth. Walter “Robby” Robinson (Michael Keaton), Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), Mike Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), and Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James) weren’t reimagined or exaggerated for drama. They were, and are, real reporters who worked the story exactly as the film shows: knocking on doors, combing through records, building cases one piece at a time. The script even lifts lines straight from their actual reporting.

The heart of the story is the team’s battle to get key documents unsealed—legal filings that would prove Cardinal Bernard Law, Boston’s top Catholic official, knew about the abuse and actively covered it up. The legal fight, the slow-building pressure inside the newsroom, the near-despair at hitting one wall after another—it’s all portrayed with the kind of realism you rarely see in Hollywood. Spotlight makes investigative reporting look exactly like what it is: frustrating, tedious, and, when it finally comes together, absolutely exhilarating.

The Spotlight team didn’t break this story overnight. It took months of following hunches, verifying leads, and pushing past institutional silence. When they finally nailed it, they didn’t just expose one priest. They exposed 87—and, later, over 250 in Boston alone. The abuse was covered up by bishops, cardinals, and even the Vatican. The problem wasn’t a few bad apples; it was an entire system designed to protect them.

For all its accuracy, “Spotlight” does take a few creative liberties. It condenses some of the timeline, simplifies some of the legal maneuvering, and folds multiple events into single scenes. It also introduces a dramatic moment that never actually happened: Mark Ruffalo’s character, Mike Rezendes, exploding in frustration and yelling, “They knew! And they let it happen!”

It’s a powerful scene, but the real Rezendes has said he never actually shouted like that. The film needed a moment of catharsis, but in reality, reporters don’t usually explode in newsroom tirades. The real process of exposing corruption is slower, more methodical, more about persistence than passion.

Another small stretch: the film suggests that in the 1990s, lawyer Eric MacLeish gave the Globe a list of 20 priests accused of abuse, and the paper ignored it. In reality, the Globe did write about the list—but they didn’t recognize the scope of the scandal at the time. The moment was added to highlight an uncomfortable truth in journalism: sometimes, the biggest stories are hiding in plain sight, buried in archives, waiting for someone to connect the dots.

Most journalism movies focus on high-adrenaline scoops—think “All the President’s Men” or “The Insider”. “Spotlight” is different. It’s about the long game. The unglamorous, grinding work of digging out the truth.

It’s also a reminder of what happens when powerful institutions go unchecked. The Catholic Church didn’t just cover up abuse; it buried it for decades, silencing victims, intimidating families, and leaning on its political power to keep everything quiet. It took relentless journalists, and a newspaper willing to back them, to break through.

The story “Spotlight” tells didn’t end when the credits rolled. After the Boston revelations, investigations exposed the same systemic cover-ups in cities and countries around the world. The Catholic Church, once seen as untouchable, was forced to reckon with its sins in a way that might never have happened without The Boston Globe.

That’s the power of journalism. And that’s why “Spotlight” isn’t just another gripping movie. It’s an essential one.

Zodiac

Zodiac

Most journalism movies follow reporters as they crack a case wide open, exposing corruption or forcing justice. “Zodiac” (2007) is the opposite. It’s about the maddening pursuit of a story that refuses to be solved. The film follows San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist Robert Graysmith (played by Jake Gyllenhaal) as he becomes consumed by the hunt for the Zodiac killer, obsessing over clues long after the police and the press have moved on.

The real Zodiac killer was a serial murderer who terrorized Northern California in the late 1960s and early 1970s, taunting police and the media with cryptic letters, ciphers, and phone calls. He claimed responsibility for multiple killings—law enforcement never confirmed the exact number—and his messages often included bizarre threats and coded puzzles. Despite an extensive investigation, the Zodiac was never caught, and the case remains one of the most infamous unsolved crimes in American history.

Director David Fincher is known for his obsessive attention to detail, and “Zodiac” reflects that. The film is meticulously researched, drawing from police reports, news archives, and Graysmith’s own books. Many scenes recreate real-life events with near-documentary precision—the way the Zodiac moved and spoke during his attacks, the exact wording of his letters, even small details like newsroom layouts and period-accurate typefaces. The film immerses the audience so completely in the world of investigative journalism that it feels like the truth.

But it isn’t, not entirely. For all of Fincher’s precision, “Zodiac” takes creative liberties, sometimes to heighten suspense, sometimes to suggest a resolution that real life never provided. The film strongly implies that Graysmith, through sheer determination, uncovers what law enforcement could not—that Arthur Leigh Allen was the killer. The final act builds toward this conclusion, ending with a dramatic moment where a witness all but confirms Allen as the Zodiac. In reality, Allen was a compelling suspect but never charged. No physical evidence linked him to the crimes, his DNA didn’t match, and law enforcement remained divided on whether he was the man behind the letters and murders. The movie makes Graysmith seem more central to the case than he was, portraying him as tracking down key witnesses and making investigative breakthroughs, when in reality, police and journalists had explored many of these leads long before he did.

Even individual scenes blur the line between fact and fiction. One of the most chilling sequences in the film is the moment when Graysmith visits the home of a potential suspect and realizes he may be trapped in the basement of the killer. This never happened. It’s pure Hollywood, a brilliant exercise in tension but entirely invented. The film also alters one of the Zodiac’s confirmed killings, the murder of cab driver Paul Stine. In reality, witnesses initially described the suspect as a Black man, leading police to search for the wrong person and costing valuable time. The movie omits this detail, likely to streamline the story.

“Zodiac” accurately captures the grind of investigative reporting. The frustration. The cul-de-sacs and dead ends. The way an unsolved mystery can take over the lives of those chasing it. But it also leans into a contradiction. It’s a movie about journalism that strays from journalism. It frames Graysmith’s theory as the answer, even though no definitive answer exists. It heightens the drama, turns speculation into fact, and presents a stronger resolution than real-life journalists and investigators ever got.

This is where “Zodiac” moves from journalistic to cinematic. The real Zodiac investigation remains open, tangled in conflicting evidence and dead suspects. But a movie needs an ending, even if the truth doesn’t provide one.

And Fincher, despite his devotion to accuracy, ultimately does what filmmakers do. He shapes reality into a compelling story, even when the real story refuses to end.

II. The Personal Toll: When the Journalist Becomes the Story

These films examine what happens when journalism stops being just a job and starts consuming the journalist. They expose the personal and professional toll of chasing the truth through deception “(Shattered Glass”), corporate pressure (“The Insider”), public backlash (“Kill the Messenger”), or moral compromise (“Capote”).

Shattered Glass

Shattered Glass

Of all the movies on this list, this is the one I know best—because I lived it. “Shattered Glass” (2003) dramatizes the unraveling of Stephen Glass, a young journalist at The New Republic who, over a period of years, fabricated dozens of stories. I was the journalist who exposed him, writing the Forbes piece that ultimately brought him down. For me, seeing “Shattered Glass” for the first time was like experiencing déjà vu in reverse. Instead of the eerie sense that I had lived these moments before, I felt the opposite—jamais vu, the unsettling sensation of reliving something familiar but with everything slightly askew.

The script described me as “clever and affable,” and on that, Steve Zahn delivered, portraying me with warmth and wit while accurately (if not comprehensively) retracing my investigation. And here’s the irony: a movie about a journalist making things up is actually one of the most accurate portrayals of journalism in Hollywood. The filmmakers nailed the mechanics of fact-checking, the inner workings of The New Republic, and, most importantly, the way Glass manipulated everyone around him. In some ways, the movie is more faithful to the truth than the Vanity Fair article it was based on. (The reporter confused my editor and me in an excerpt of dialogue he included. Worse, he implied that Glass was a repressed gay man, which was both unfounded and deeply unfortunate.) But almost no one remembers the Vanity Fair article. They do, however, remember the movie.

I visited the set in Montreal while they were filming and watched the now-infamous conference call scene, where I confronted Glass over the phone about his many lies. After a few takes, director Billy Ray pulled Hayden Christensen, who was portraying Glass, aside. He told him, “Play this scene as if you really, truly believe what you’re saying.” And it transformed the moment. Christensen delivered the lines with complete conviction—no guilt, no hesitation, just the certainty of someone who hadn’t only fooled thousands upon thousands of readers. He had fooled himself.

This enabled him to live with himself despite a near constant stream of lies issuing from his pen. Because Glass didn’t just fabricate a few quotes. He made up an entire article, complete with fictional sources, fake companies, and elaborate cover-ups. His piece “Hack Heaven,” the one that first caught my attention, had a Hollywood-ready narrative that was almost too good to be true, which involved a teenage hacker blackmailing a software firm.

As I dug into the details, nothing checked out. Jukt Micronics, the company at the center of his story, didn’t exist. Neither did any of the sources. The supposed hacker convention? Pure fiction. The New Republic had a fact-checking system, but it relied on reporters providing their own notes—something Glass exploited by faking voicemails, forging documents, and even impersonating sources when questioned.

When I confronted The New Republic about the inconsistencies, it set off a slow-motion collapse. As they pressed Glass for proof, his explanations became increasingly absurd, until he finally admitted he had been fabricating stories for years.

How well does the movie get the facts right? Impressively well. It didn’t come close to giving a full accounting of all the research we did, but that wouldn’t be very cinematic anyway. There was no Rosario Dawson at Forbes.com. Believe me, if there had been, I would have remembered. She was a composite based on several colleagues who pitched in with the research. And no one ever asked to share the byline with me.

What “Shattered Glass” captures brilliantly is the psychology of deception. Glass wasn’t just lying—he was manipulating. He made himself indispensable to his colleagues, played the victim when cornered, and turned his self-deprecation into a shield. Even when caught, he clung to the idea that he could somehow talk his way out of it.

It also gets newsroom politics right. The New Republic was a small, prestigious magazine run by a young staff with little oversight. Editors trusted their writers, and Glass exploited that trust. His boss, Charles Lane, had to push past his own biases to accept that his rising star had been conning him all along.

Most journalism movies are about heroic reporters exposing corruption. “Shattered Glass” is the opposite—it’s a cautionary tale about what happens when a journalist betrays the profession. It exposes the vulnerabilities in newsroom oversight, the seductive power of a well-told story, and how easily a fraud can thrive when no one asks the right questions.

The best journalism films show why the truth matters. “Shattered Glass” shows what happens when it doesn’t.

The Insider

The Insider

Russell Crowe is a formidable actor—intense, meticulous, and capable of disappearing into a character. He doesn’t merely play a role. He inhabits it.

How do I know? Years ago, I found myself in a small classroom at Central Michigan University, waiting to give a lecture on journalism ethics. The school had sprung for dinner—sandwiches, nothing fancy—but as I sat there, I noticed a man had grabbed mine. Whatever. I didn’t say anything. I just took his.

As I picked cheese slices off my sandwich we chatted, and something gnawed at me. He reminded me of someone. But I couldn’t place it. Then it clicked. Oh, yeah, I thought. He looks and sounds like that guy from that movie, The Insider. Who was it again? Oh, right—Russell Crowe. Then I realized: I wasn’t talking to an uncanny lookalike. I was talking to Jeffrey Wigand—the actual insider from The Insider, the man Crowe had so convincingly portrayed.

I had never encountered Wigand before, only Crowe’s version of him, yet the performance was so spot-on that I recognized the real man based solely on the movie. That says everything about Crowe—not just as an actor, but about how movies can reshape reality until a performance can feel more real than the person.

“The Insider” (1999) tells the story of Wigand, a former tobacco executive who blew the whistle on tobacco industry efforts to manipulate nicotine levels and suppress health risks. His revelations formed the backbone of a 60 Minutes exposé, but the real drama happened off-camera. CBS, under pressure from corporate lawyers and fearful of a billion-dollar lawsuit, nearly killed the story.

This wasn’t the government censoring the press. It wasn’t a legal gag order. This was a news organization voluntarily pulling its own investigation because it feared financial consequences. That’s what makes The Insider unique among journalism movies—it’s not just about exposing wrongdoing. It’s about the internal war that happens when a news division collides with corporate interests.

How close did the movie get to the real story? In broad strokes, it nailed it. The scenes where 60 Minutes producers fight with CBS executives, the legal hand-wringing over potential liability, the way Wigand’s credibility is attacked—those all happened. The movie captures the immense pressure investigative journalists face, not just from the powerful entities they expose but sometimes from their own employers.

That’s not to say there weren’t liberties taken. Al Pacino’s character, producer Lowell Bergman, is depicted as the relentless champion of the story, fighting tooth and nail to get it on the air. In reality, Bergman did push hard, but 60 Minutes anchor Mike Wallace was far more conflicted than the movie suggests. The film paints him as weak, complicit in CBS’s decision to pull the segment, but those who were there say it was more complicated.

Still, the essence is true: CBS hesitated. Lawyers won out over journalists. And for a time, it looked like a major investigative scoop might never see the light of day.

Most journalism movies pit reporters against external forces—corrupt politicians, abusive institutions, powerful corporations. The Insider flips the script. The enemy isn’t just Big Tobacco; it’s fear, bureaucracy, and the bottom line. It’s a reminder that the struggle for truth doesn’t just happen outside the newsroom. Sometimes, the biggest fight is within.

When the movie ends, Wigand has lost almost everything—his job, his marriage, his anonymity. But he did the right thing. And in the end, the story did air. Not because CBS wanted it to, but because The Wall Street Journal got hold of the evidence and forced their hand.

It’s an important lesson. Journalism is only as strong as the institutions willing to stand behind it. And sometimes, the hardest battle isn’t learning the truth—it’s making sure the truth gets told.

Kill The Messenger

Kill The Messenger

Most journalism movies celebrate reporters as dogged truth-seekers who expose corruption and bring down the powerful. “Kill the Messenger” (2014) tells a different kind of story. It’s about what happens when a journalist takes on a story too big, too dangerous, and too politically explosive, and instead of fame or glory he’s greeted with professional ruin.

The film follows Gary Webb, an investigative reporter for the San Jose Mercury News, who in the mid-1990s uncovered a shocking connection between the CIA and the crack cocaine epidemic ravaging American cities. His reporting suggested that the agency had turned a blind eye—or worse, was complicit—as Nicaraguan drug traffickers funneled cocaine into the U.S. to help fund the Contras, the anti-communist rebel group backed by the Reagan administration. It was the kind of bombshell that should have sparked congressional hearings, outraged editorials, and serious government reform. Instead, Webb became the story, targeted by a coordinated effort to discredit him and his work.

The film gets many aspects of investigative journalism right, particularly how lonely and exhausting the work can be. Webb (played by Jeremy Renner) isn’t a high-profile political reporter at a national outlet; he’s a local journalist with a nose for corruption and a willingness to follow leads others ignore. He does the kind of digging real investigative reporters do—chasing documents, badgering reluctant sources, and traveling to Central America in search of the truth. He uncovers damning evidence, but instead of being celebrated, he’s met with skepticism, not just from the government but from his own profession.

One of the most accurate aspects of “Kill the Messenger” is how it depicts the backlash Webb faced. At first, major newspapers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times largely ignored his reporting. But once the story gained traction, those same outlets didn’t try to build on Webb’s investigation. They tried to tear it down. They poked holes in his sourcing, questioned his conclusions, and ultimately cast doubt on the entire premise of his work. The film effectively captures how powerful institutions—whether government agencies or legacy media—can close ranks when they feel threatened. Instead of investigating the CIA’s possible involvement in the drug trade, the biggest newspapers in the country investigated Gary Webb.

This wasn’t just professional rivalry. Webb’s story implicated the same mainstream media organizations that had ignored or downplayed similar allegations years earlier. His reporting suggested they had either missed or buried one of the biggest scandals of the decade. Rather than admit that possibility, they focused on undermining Webb’s credibility. The film dramatizes this dynamic well, showing how quickly public perception can turn against a journalist once the weight of institutional power is applied.

That’s not to say “Kill the Messenger” gets everything right. It simplifies some of the more complex aspects of Webb’s reporting and legal struggles, and it paints his editors at the Mercury News as caving to pressure more quickly than they actually did. In reality, Webb’s editors initially stood by him, but as the backlash grew, they distanced themselves from the story. Eventually, Webb was reassigned to a suburban beat. It was a humiliating demotion for a once-prominent investigative journalist. Feeling abandoned by his profession and struggling with personal issues, Webb ultimately took his own life in 2004.

The larger takeaway from “Kill the Messenger” is chilling: when powerful interests feel threatened, they don’t just deny stories. They destroy the journalists who report them. The CIA even went to the trouble to classify the script as “Top Secret”. Webb’s work was never entirely disproven, and years later, internal government reports confirmed much of what he had alleged. But by then, the damage was done. His career was in ruins, and his reporting was widely dismissed as conspiracy theory. The film serves as both a tribute to Webb and a warning about what happens when the truth is inconvenient to those in power.

Unlike the journalists in “All the President’s Men” or “Spotlight”, Webb didn’t have the backing of a major newspaper or a team of colleagues to shield him from attack. He was one reporter, working for a regional paper, up against the full weight of the government and the national press. “Kill the Messenger” captures that reality, showing that the greatest threat to journalism isn’t just censorship. It’s the systematic discrediting of those who dare to ask the wrong questions.

Capote

Journalism is supposed to be about the pursuit of truth. But what happens when a journalist becomes so consumed by a story that truth becomes secondary to storytelling? “Capote” (2005) is about that uneasy line—how Truman Capote, in writing the landmark book, “In Cold Blood”, didn’t just document a crime. He manipulated it.

Published in 1966, Capote’s book was a groundbreaking literary event. It became a massive bestseller, widely credited with inventing the nonfiction novel—a new form of journalism that borrowed the techniques of fiction. Vivid scene-setting, reconstructed dialogue, deep psychological insight—these were hallmarks of In Cold Blood. But so was its greatest controversy: Capote’s willingness to prioritize narrative over fact. He blurred the lines, editing reality for effect, making the killers more sympathetic, shaping real events into a structured, cinematic story. The book became a cultural touchstone, assigned in classrooms, studied for its style, and debated for its ethics.

“Capote” the film follows him as Capote the man embeds himself in Holcomb, Kansas, after the 1959 grisly murders of the Clutter family. He arrives as a journalist, researching a New Yorker article, but quickly becomes something else: a confidant to one of the killers, Perry Smith, and an architect of a narrative that suited his needs.

The film captures how he gained Smith’s trust—not to seek justice, but to shape him into a character. He encourages Smith to open up, coaxing out painful childhood memories and poetic reflections on violence. Yet when Smith asks if Capote can help with his appeal, Capote dodges, offering vague reassurances while privately hoping for an execution. He needs Smith to die so his book can have an ending.

This is where “Capote” forces us to confront the ethics of literary journalism. Truman Capote blurred fact and fiction, reconstructing entire scenes, inventing dialogue, and omitting inconvenient details. Unlike traditional journalists, bound by strict accuracy, he crafted a story first and fit the facts as needed. Did In Cold Blood expose corruption? No. Did it reveal systemic failure? Not really. It wasn’t investigative journalism—it was an experiment, a novel dressed as fact.

The film suggests Capote understood exactly what he was doing—and that it may have destroyed him. After In Cold Blood, he never finished another book. He descended into alcoholism, alienated his friends, and seemed increasingly haunted by his choices. His masterpiece came at a cost.

But do we know this to be true? We know In Cold Blood was the peak of Capote’s career, that he never completed Answered Prayers, that his personal life unraveled, and that those close to him believed the Kansas case changed him. But was it In Cold Blood that broke him? Or was he always on a path toward self-destruction? Capote never said.

The film presents his downfall as inevitable, but is that because it’s fact—or because it makes for a better story?

If we assume cause and effect without confirmation, aren’t we guilty of the same thing Capote was?

III. The Mission: Journalism in the Face of Power and Danger

These films remind us why journalism matters. They follow reporters who take on the most dangerous stories—whether exposing a political witch hunt (“Good Night, and Good Luck”), covering war crimes (“The Killing Fields”), or risking everything to bear witness (“A Private War”).

Good Night, and Good Luck

Good Night, and Good Luck

Most journalism movies are about reporters chasing a story. The 2005 film, “Good Night, and Good Luck”, is about something bigger: the fight to keep journalism itself alive. Filmed in stark black and white, it captures a moment when television news wasn’t just informing the public. It was defining its own role in American democracy.

The film centers on Edward R. Murrow, the legendary CBS broadcaster who took on Senator Joseph McCarthy at the height of the Red Scare. In the early 1950s, McCarthy had built his power on paranoia, smearing public figures as communist sympathizers and ruining lives with reckless accusations. Few dared to challenge him. That was until Murrow did. His “See It Now” broadcasts exposed McCarthy’s tactics for what they were: bullying, fearmongering, and a fundamental threat to American values.

David Strathairn plays Murrow with a quiet, steely intensity, delivering his signature sign-off, “Good night, and good luck”, with the weight of a man who knows he’s putting his career on the line. The film, which George Clooney directed, captures the tension inside CBS as Murrow and his producer, Fred Friendly (played by Clooney himself), push forward with their reporting despite corporate and political pressure to back off.

Murrow himself, however, would have told a different version of the story. Later in life, he was clear-eyed about his role in McCarthy’s downfall, downplaying his own significance: “We merely said, ‘The emperor has no clothes.’ The credit belongs to the reporters in the field who had been exposing McCarthy long before we put him on television.” He knew his broadcasts had an impact, but he also recognized that McCarthy’s collapse was already in motion. This was thanks in large part to print journalists who had spent years chipping away at his credibility. “Good Night, and Good Luck” turns Murrow into a lone warrior, but in reality, he was just the most visible figure in a much larger battle.

The film also simplifies the consequences Murrow faced. Yes, CBS lost sponsors, and yes, the network grew more cautious in the wake of the McCarthy broadcasts. But Murrow’s greatest frustration wasn’t political pushback. It was television itself. He saw what was coming. The shift from serious reporting to entertainment. The slow erosion of public affairs programming. The creeping influence of advertisers over editorial decisions. He warned about all of it in his famous 1958 speech to the Radio-Television News Directors Association, which “Good Night, and Good Luck” uses as a framing device:

“This instrument can teach, it can illuminate; yes, and it can even inspire. But it can do so only to the extent that humans are determined to use it to those ends. Otherwise, it is merely wires and lights in a box.”

That speech wasn’t about McCarthy. It was about television itself, and how Murrow feared it was squandering its potential. He worried that broadcast news, instead of being a tool for enlightenment, was becoming an amusement machine. And he was right. By the early 1960s, he had left CBS, frustrated by corporate interference and the shrinking space for real journalism.

One wonders what Murrow would make of today’s cable news landscape, where insta-opinion drowns out investigation and the crackling soundbite matters more than the truth behind it. He warned of television becoming a distraction rather than a public service. What would he say now, in an era when the “wires and lights in a box” have multiplied into an endless digital stream, where news is consumed in fragmented bursts on phones, pushed by algorithms that favor outrage over accuracy?

What would he make of the clickerati, the army of social media personalities who drive the conversation not by reporting the facts, but by shaping them into viral takes designed to provoke rather than inform? Murrow fought against a government that weaponized fear. What would he make of a world where misinformation spreads faster than the truth, not because of state suppression, but because we ourselves choose the version of reality we like best?

Murrow didn’t see himself as a hero. He didn’t view “See It Now” as a crusade. He was a journalist doing his job by asking tough questions, holding power to account, and making sure the public had the information it needed. “Good Night, and Good Luck” captures that spirit, but it also gives Murrow more credit than he gave himself. He saw McCarthy as a symptom, not the disease. The real danger wasn’t one rogue senator. It was the way fear and complacency let him operate unchecked.

The movie is a reminder that journalism doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It depends on institutions willing to support it, audiences willing to listen, and journalists willing to take risks. Murrow had all three, at least for a while. But he knew better than anyone that truth alone isn’t always enough.

The bigger battle, the one he warned about, the one we’re still fighting today, isn’t just about getting the story. It’s about making sure there’s still a place to tell it.

The Killing Fields

The Killing Fields

Some journalism movies are about the thrill of the chase. “The Killing Fields” is about survival. It’s about what happens when a reporter’s job stops being about breaking a story and starts being about staying alive. It is, at its core, a war film—but instead of soldiers, its protagonists are journalists, and instead of battlefield heroics, it shows the brutal, inescapable reality of covering war in an authoritarian regime.

The film, released in 1984, tells the true story of New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg and his Cambodian assistant, Dith Pran, as they cover the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge in 1975. Schanberg (played by Sam Waterston) represents the Western war correspondent—idealistic, determined, and ultimately insulated from the full consequences of the conflict. Dith Pran (played by Haing S. Ngor, a real-life survivor of the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror) is the local journalist, the fixer, the translator, the man whose knowledge of the land and its people makes the reporting possible. And, as the film makes painfully clear, he is also the one who pays the highest price.

This is one of the most unflinching portrayals of war reporting ever put on screen. It doesn’t glorify journalism. It doesn’t make reporters out to be heroes. It simply shows the truth: that covering war is terrifying, unpredictable, and often fatal. Schanberg, like many Western correspondents, has the luxury of fleeing when Phnom Penh falls. Pran does not. He is left behind, captured by the Khmer Rouge, and forced into the brutal labor camps where nearly two million Cambodians would die during the regime’s genocide. His only crime was his association with Western journalists.

“The Killing Fields” is brutally accurate in its depiction of what foreign correspondents face in conflict zones. War reporters don’t just risk being caught in the crossfire; they risk becoming targets. Authoritarian regimes, insurgent groups, and even democratic governments see journalists as threats, and too often, they are treated as enemies. The film captures the paranoia, the desperation, and the moral weight of covering atrocities—something war reporters today still confront in places like Syria, Ukraine, and Gaza.

That said, the film, like many journalism movies, simplifies some of the realities of war reporting. While Schanberg is portrayed as deeply devoted to Pran, there has been criticism that the film places too much emphasis on the American journalist’s guilt rather than on Pran’s own agency and survival. In reality, Pran’s journey through the killing fields of Cambodia—his escape, his resilience, his sheer will to live—is the heart of the story. But Hollywood needed a Western anchor for the audience, and so the film spends more time on Schanberg’s anguish than it does on Pran’s suffering.

Still, what “The Killing Fields” gets undeniably right is the cost of bearing witness. Journalism in war zones isn’t just about telling stories—it’s about staying alive long enough to tell them. And even then, the truth doesn’t guarantee justice. The Khmer Rouge’s crimes were among the worst of the 20th century, but the world’s response was muted. The reporting didn’t stop the genocide. It didn’t bring the dead back. But without journalists like Schanberg and Pran, we might never have known the full scale of what happened.

That’s the larger takeaway of “The Killing Fields”. Foreign correspondents don’t just risk their lives—they trade their safety for the possibility that the world will pay attention. And all too often, the world does not.

Yet they keep going. Because if they don’t, no one will.

A Private War

A Private War

Most journalism movies focus on reporters exposing corruption or chasing a once-in-a-lifetime scoop. “A Private War” is about something else—the cost of bearing witness. It follows the real-life story of Marie Colvin, the legendary war correspondent for UK’s The Sunday Times, whose fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflicts made her both famous and deeply haunted.

Rosamund Pike plays Colvin with an intensity that captures both her brilliance and her self-destruction. The film shows her navigating war zones, interviewing rebels and refugees, and always pushing to get closer to the truth, no matter the risk. It also doesn’t shy away from the personal toll of her work—her alcoholism, her fractured relationships, and the PTSD that she tried, and often failed, to suppress.

“A Private War” is brutally honest about what it means to be a war reporter. Covering conflict isn’t just about storytelling—it’s life or death. Colvin lost an eye while reporting in Sri Lanka, but rather than pull back, she doubled down, wearing an eyepatch as a badge of honor and throwing herself into even more dangerous assignments. The film gets this part right: for many war correspondents, journalism isn’t just a job. It’s a compulsion, an addiction. The need to be there, to see, to tell the world what’s happening becomes stronger than the instinct for self-preservation.

The film also does an exceptional job portraying the emotional cost of Colvin’s work. Unlike other war films that focus on battlefield heroics, “A Private War” shows what happens after the assignments—when the adrenaline fades and the trauma lingers. Colvin suffered from PTSD, and the movie doesn’t flinch from showing how it affected her. She drank heavily, struggled with relationships, and fought against the very idea of slowing down. Her bravery wasn’t just about walking into war zones—it was about living with what she saw and refusing to turn away.

But does the movie over-romanticize her? Maybe. It leans into the idea of the lone war reporter, the fearless truth-seeker who puts everything on the line for the story. In reality, journalism is rarely a solo act. Colvin had fixers, editors, and photographers who helped make her reporting possible, including Paul Conroy, the photojournalist who was with her when she was killed in Syria in 2012. The film captures their relationship but, like many journalism movies, simplifies the reality of how these stories get told.

The larger question “A Private War” raises is whether there’s a line between bravery and recklessness. Where does duty end and self-destruction begin? Colvin was undoubtedly one of the most courageous reporters of her time, but she was also deeply aware of the risks she took. In one scene, she says, “I see it so you don’t have to.” That, in many ways, was her guiding principle.

She died doing exactly what she believed in—reporting from a besieged Syrian city as bombs fell around her. The film makes clear that her death wasn’t an accident. The Syrian government deliberately targeted the makeshift media center where she and Conroy were working. It was a direct attack on journalism itself.

That’s why “A Private War” matters. It’s not just a tribute to Colvin. It’s a reminder of what war reporters risk every time they step into a conflict zone. And it forces us to ask a hard question: How much truth is worth a life?

For Marie Colvin, the answer was always the same. All of it.